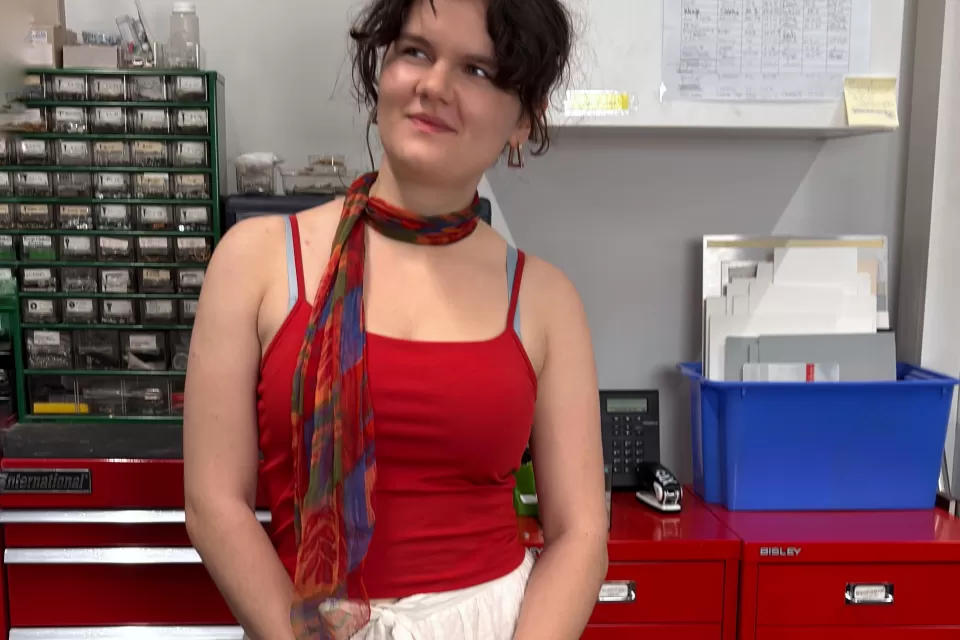

© Veronika Dirnhofer

Studio Drawing: Interview with Veronika Dirnhofer

Author: Amar Priganica (UGC)

In the three parts of the first episode of his academy podcast, student Amar Priganica interviews Veronika Dirnhofer, professor of the drawing studio at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.

Application and Portfolio

In the first part of the episode, Veronika Dirnhofer provides insights into her artistic practice and the work in her class. She also talks about the application process at the academy and shares her experiences and thoughts on the subject of application portfolios — a crucial step for many prospective students.

Text to Part 1

Welcome to the Academy Podcast of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. My name is Amar Priganica, and today we’re very lucky to be speaking with Veronika Dirnhofer — she’s the professor heading the studio Art and Image | Drawing.

Uh, since this is really the very, very first episode, I’ll quickly explain the concept — for everyone who doesn’t know it yet… which is basically everyone. So: it’s a podcast format for the Academy Kiosk, featuring teachers from the Academy of Fine Arts. It’s aimed at applicants who want to learn more about the Academy — and also why you should apply here… or maybe not.

The idea is to keep the whole thing to a maximum of 15 minutes so it’s actually digestible in our… um… non-existent attention economy. Kind of a counter-model to all those four-hour podcasts out there.

Right. I already had a Red Bull earlier to try to talk or think faster — didn’t work quite as wonderfully as I imagined. But let’s just start.

So, hello Veronika, great to have you here! Could you please introduce yourself again in your own words, if that’s possible?

Right, I’m Veronika Dirnhofer, as you said, I head the Drawing class here at the Academy, one of — I think — 17 classes at the Institute for Fine Arts. I’ve been at the Academy for many, many years, I know it very well, and I do this job — yes, it’s a job — but I really love it. It’s a fantastic place with amazing people and… it’s just good.

Maybe let’s start at the beginning. You said you’ve been at the Academy for a long time — did you also study here?

Yes, I studied here, but in the Abstract Painting class. Then I left, but came back as an assistant — which is rather rare. I worked as an assistant for a very long time, did my habilitation, and then took over the Drawing class.

How does one actually become a professor of art?

Not automatically, unlike some might think. Usually it’s through an open call: you have to do a hearing and go through several stages. Then a committee makes the decision.

And the Drawing class hasn’t existed for that long, right? How did it come about that a new class was created?

Well, when I studied here there were only eight classes altogether, including Sculpture. Over the years the Academy grew; there are development plans written by the Senate. Back then, the Graphics/Printmaking class was extremely overrun, and the decision was made to create an additional class for Drawing. Drawing has many offshoots — tentacles, so to speak — in all directions. It can be a very broad field. The Rectorate — I believe under Rector Blimlinger — decided this together with the Senate.

I find that interesting because… I studied in the Painting class with Daniel Richter. And there, I often felt that drawing was seen as a bit inferior — just a derivative, a preliminary study. Everyone draws, but it’s considered half-finished. So: what does drawing mean to you personally?

That opinion — that drawing is merely a preliminary step to painting — still exists, but in my understanding of art, we’ve really moved beyond it. I see drawing as something very independent and very democratic: everyone can draw, and it barely needs resources. You can see text as drawing; you can map, denote, distort; you can draw concepts; you can draw collectively… There are so many possibilities. At the same time, it ranges all the way to extremely delicate figurative or fictional drawings that can open up a whole world on one square meter. That range is what makes drawing so exciting for me.

And what happens concretely in your class? Do students have studio spaces with drawing tables, or how should we imagine it?

So, at the beginning — the admissions — we look at the portfolios. This year there were around 1,600 applications overall, about a third for the “Art and Image” area. We specifically look for people who work in a drawing-based way, not only painting. So drawing is the basis, but over the years many students develop in other directions: filmic, installation, painting. Two of five current diplomas are very drawing-based; the others go into sculpture or installation. There’s no “ban on painting” — people develop their work as they must.

And the admissions — are portfolios digital now or back to physical?

We switched to pdfs after COVID, but we fought to have at least the second round in person again. I’m not a fan of pdfs; works can be distorted on screen. Sometimes you think it’s huge, and then it’s tiny. But for applicants it’s an advantage: they can apply to ten international schools at once. In the past you had one physical portfolio that you could hardly ship around.

People say lots of portfolios are 90% manga or horse drawings. Is that true?

Partly, yes. But that also has to do with what’s taught in schools. I don’t want to blame the young people alone. We do see many portfolios where it’s quickly clear: not a fit. At the same time, there are genuinely great works. Pdfs help applicants look professional, but for us it’s harder to judge.

If someone is interested in your class, can they sit in on a class meeting?

Well, it would be unfair if I gave selected applicants special access. I helped found the working group for equal treatment here, and that matters to me. Sympathy doesn’t play a role in admissions — we want fair chances for everyone. Resources are limited: studio spaces, workshops. So I think it’s wrong to let people in through a side door.

Everyday student life, parties, and activism

The second part of the podcast episode with Veronika Dirnhofer, professor of Art and Image | Drawing at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, focuses on everyday life in her class. She talks about the structure and layout of the studios, class meetings, and how working together shapes everyday student life. Another topic was activism in art and the series of parties organized by the drawing class to collect donations for Ukraine.

Text to Part 2

Mhm. And once you’ve actually made it into the Drawing class — what does everyday life look like?

We already touched on this: everything is tailored very individually. That’s why it’s a good place to study — you have to figure out what you want yourself.

I heard — and found it really interesting — that you actually allocate the workspaces in the class. So not this “survival of the fittest,” where whoever pushes hardest gets the best spot.

Yes, exactly. We assign places — sometimes for a year, sometimes a semester. People go on Erasmus, new people arrive. I think everyone should have a decent workspace. If someone doesn’t use their spot for a long time, we may step in and give it to someone else. We also think about who fits with whom, so it’s not always the same group clustered together. That’s important to us because we fought for the diploma system — we didn’t want the bachelor-master split. We value learning across cohorts. If first-semester students sit next to diploma candidates, both sides learn a lot.

And the class meetings — how often, and what happens there?

We meet every Wednesday, very regularly. It takes a big exception for us to skip it. We start by discussing current topics, often societal ones. We’re a very international class — students from Ukraine, Ghana, Bangladesh, the US… lots of perspectives. After that, there are presentations of works. We practice critique — but respectfully. It’s about learning to give and to receive critique; both are essential.

Okay, interesting. My “secret informant” from the class told me environmental issues are super important for you — both artistically and in the class ethos. True?

Absolutely. I call it “transformation,” and it’s a focus in the class. Not because I thought, “we need a topic,” but because it’s the most existential crisis of our civilization. And we in the Global North are the cause. The topic is highly intersectional — feminism, distributional justice, health, ecology, wealth. We invite guests, go to exhibitions, discuss. There’s no obligation that it shows up in the artwork, but we do engage with it. I’ve talked to climate scientists who said: we need artists to build new narratives against the fossil ones. We all know the fossil narratives — Hollywood, advertising, status symbols. But what is another good life? That’s where art can step in.

Where’s the boundary between art and activism for you?

For me, everything should be possible — subtle, metaphorical, or openly activist. But to reach people you need emotion. I envy musicians, because music can deliver emotion in seconds. In visual art it often takes longer, but it has always told stories. We need new stories, especially on this topic.

You said you’ve been moved to tears by art. Which works were those?

El Greco and Mark Rothko. I saw Rothko in New York — that room completely overwhelmed me. Of course it’s individual; it also depends on your own state. In music, the collective experience happens faster, I think. But visual art can do it too.

And then there was the Ukraine action in your class. Could you tell that story again?

Yes. For me, it’s simple: we’re always in the middle of things. Everything is political — what I eat, what I buy, how much I pay for rent. Also whether there’s a war in Ukraine or not. When the invasion started in 2022, it was a shock. We decided as a class: we’ll do something. Besides donations in kind, we organized courtyard parties — with music, DJs, everyone helped. In the end we donated 22,500 Euros to various organizations, some very small ones that were directly distributing food in Ukraine. It was a powerful experience for the class.

Art, Politics and Expectations

The third part of the podcast episode with Veronika Dirnhofer deals with central questions about the role of art in our time. We talked about activism in art, identity politics, the social significance of artistic practice, and the pressing issues of climate change. Finally, we returned to the expectations that applicants to the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna “should” have.

Text to Part 3

There are people who say art should be otherworldly — escapist rather than activist. Dean Kissick wrote a piece in Spike looking back nostalgically at the 2000s: big Carsten Höller slides in the Hamburger Bahnhof, Prosecco with Hans Ulrich Obrist — art as decadence, wonder, world-forgetting. And he argues that today’s seriousness, identity politics, activism — that it harms art. Can you relate to that?

Hmm, partly. It wasn’t “all good” back then either. There was 9/11, wars, environmental destruction — a lot was already visible. But today it’s ever-present because of social media. You’re constantly confronted. And yes, sometimes I get angry when I read scientific articles on the climate crisis and at the same time see the art bubble jetting around while posturing as hyper-aware. But: it’s still important that wonder remains possible. Art should also create spaces for puzzlement, for the unknown.

Last question: what advice would you give applicants interested in your class or the Academy in general?

The most important thing: the work has to be interesting. That’s the basis. But then I also look at how people perceive the world. Do they like working in groups? Are they curious — obsessed enough to really want to be in the studio every day? If not, this might be the wrong place. There are many other exciting careers that are easier. Art is hard; the bottleneck after graduation is even narrower than the entrance exam. Galleries, jobs — very difficult. But: if you truly can’t help it, if you suffer when you don’t get to the studio — then you belong here.

So career prospects are rather tough?

Yes, it’s not easy. But I firmly believe this: a society in which many people have studied art is a better society. People are more reflective, less susceptible to right-wing ideologies. And I do see many alumni who make their way — often modestly, sometimes precariously, sometimes with support. But not hopeless.

A personal question: are there any right-wing students at the Academy?

In my class, definitely not. I can’t speak for all institutes, but with us it’s not an issue. We live diversity, and I think that’s wonderful.

Okay, great. Thanks so much!

Thank you — that wasn’t bad at all.

Amar Priganica is a student in the doctorate program of Philosophy at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.

Further articles

Studying Fine Arts: An ASMR Visit to the Studio of Art and Image | Drawing

Author: Maria Pylypenko (UGC)

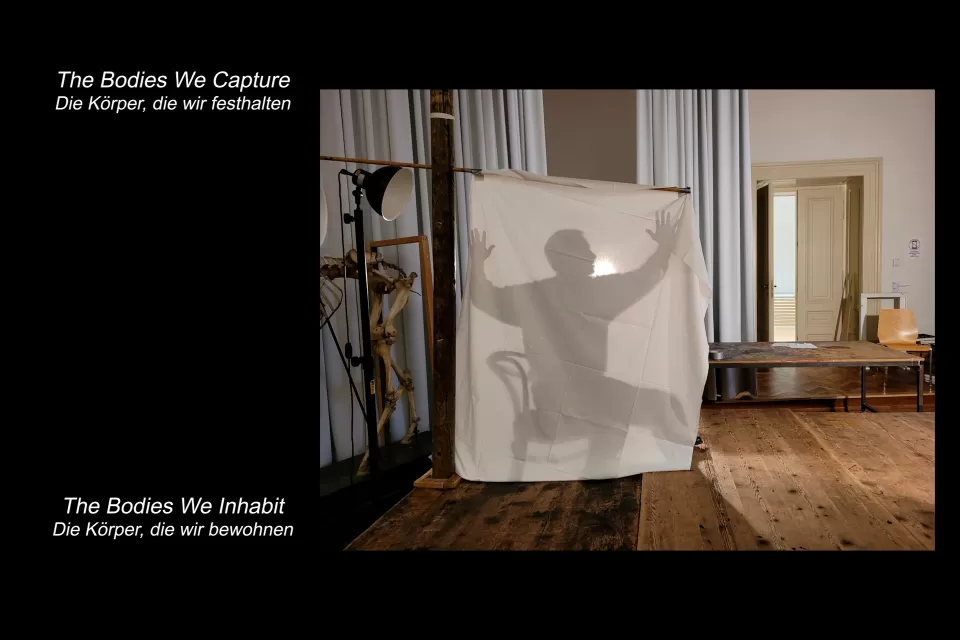

The Bodies We Capture, the Bodies We Inhabit

Author: Ali Amiri (UGC)